By Hannah Ostroff

On a chilly evening, a limousine glides up to the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. A door opens, and a presidential foot plants itself on the red carpet stretching up to the building’s entrance. His staff swarms around while cameras flash and reporters elbow eagerly to ask a question of the president. A nod. A wave. A twinkle in his eye.

Except this isn’t a real president.

It’s an actor, portraying a president, on the evening of the unveiling of his portrait in the museum’s collection.

But it’s not a presidential portrait, either—at least not one that will hang in the “America’s Presidents” exhibition of the museum.

A new portrait of Kevin Spacey in his role as “House of Cards” President Francis J. Underwood was unveiled Feb. 22 at the National Portrait Gallery. The portrait is a joint project between British artist Jonathan Yeo and the museum, which houses the only complete collection of presidential portraits outside of the White House. (Photo by Paul Morigi)

The true story: The National Portrait Gallery collaborated with artist Jonathan Yeo who was working on a portrait of actor Kevin Spacey. Yeo and Spacey decided to depict the actor as his character, President Frank Underwood from the Netflix series “House of Cards.” When it came time for the museum to unveil the piece in February, they staged an event worthy of a president, complete with Spacey arriving and addressing guests as Underwood.

Spacey’s is not the only portrait in the collection where an actor is depicted in character, but this one in particular speaks to major changes in how Americans consume TV in an age of streaming and binge-watching. For Yeo, making art from a living subject is similar to an actor playing a role, blurring the boundary between real life and fiction.

To learn more about the history of this style of portraiture, we talked to Robyn Asleson, assistant curator in the Department of Prints, Drawings and Media Arts of the National Portrait Gallery.

Q: What’s the history of portraying actors in character?

Asleson: Portraits of actors in character flourished in Europe throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Then as now, the tremendous celebrity of actors generated demand for their images—most often as they appeared on the stage, in costume and in character.

Ira Aldridge as Othello, painted by Henry Perronet Briggs (oil on canvas, c. 1830). (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

The rich bought paintings and others bought less expensive prints. Plays were published with frontispiece illustrations of whatever actor happened to be playing the lead role at the time of publication, shown in character.

Theatrical celebrity was slower to catch on in America, though. When the English portraitist Robert Edge Pine immigrated to America in 1784 he brought with him a collection of portraits he had painted of famous English stage performers in character. Pine launched his career by putting these theatrical portraits on display in Philadelphia.

Q: Why does the National Portrait Gallery include portraits of actors as their characters?

Asleson: Portraitists represent more than the physical appearance of their subjects. They provide insights into their occupations, interests, and achievements, often by showing their subjects engaged in characteristic activities or surrounded by defining objects. Musicians are shown with their instruments, athletes in uniform, dancers dancing and actors acting.

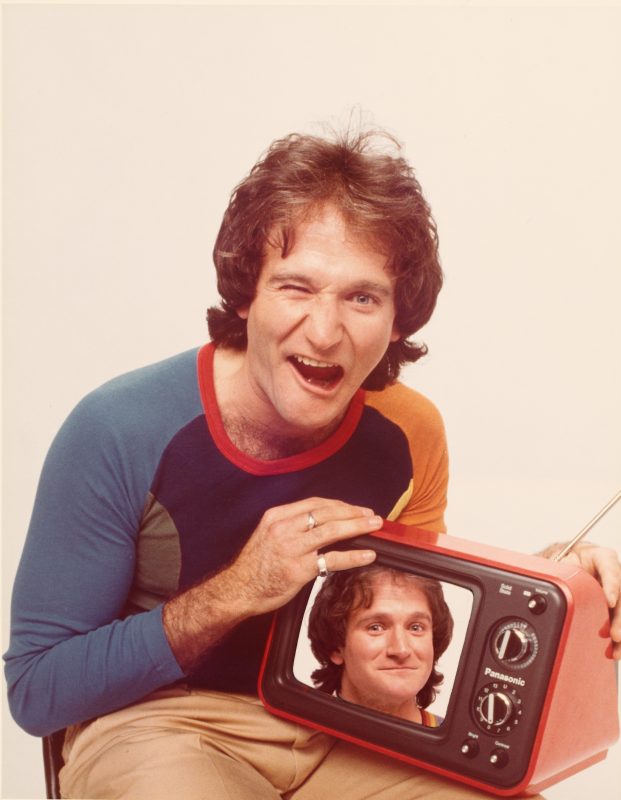

Robin Williams by Michael R. Dressler, (Chromogenic print, 1979). (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Time magazine. Conserved with funds from The Pritzker Traubert Family Foundation)

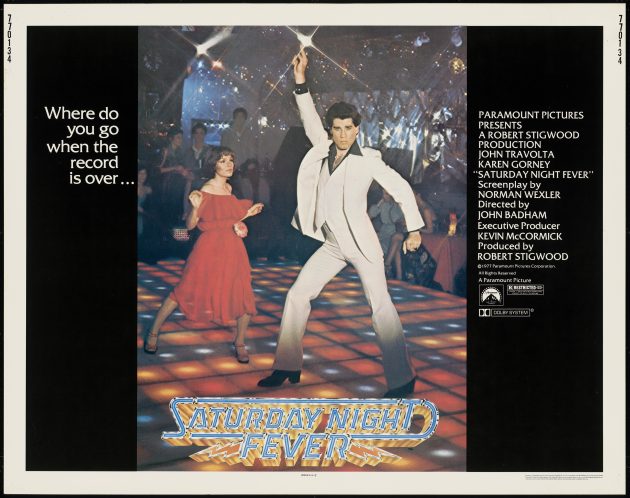

Portraits of actors in character also help define a particular moment in their careers. Robin Williams appearing as Mork, for example, or John Travolta as Tony Manero in “Saturday Night Fever.”

Q: Why are these portraits meaningful to the museum, and how do they represent the legacy of the performers?

Asleson: The mission of the Portrait Gallery is to tell the story of America, and many of our most culturally resonant stories are based on fictional characters personified on the stage and screen by talented actors.

Several of the Portrait Gallery’s earliest acquisitions were portraits of actors in character, such as Paul Robeson as Othello (given to the museum in 1967) and Ethel Merman as Annie Oakley (a gift of the sitter in 1971).

Ethel Merman by Rosemarie Sloat (oil and acrylic on canvas, 1971). (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Ethel Merman)

Some of these actors are better recognized in character than as themselves. Examples include Charlie Chaplin as The Little Tramp, John Wayne as Rooster Cogburn in “True Grit” and Sylvester Stallone as Rocky Balboa.

Q: Do curators ever seek out portraits of actors in character? Why or why not? What is the process like, and does it differ from a traditional portrait?

Asleson: We are constantly adding to an extensive collection of portraits of actors in character that includes theatrical posters, publicity photographs, cartes de visites, caricatures, drawings, and engravings dating from the early 19th century to the present day. In fact, searching under “actor” brings up 1,815 hits for the Portrait Gallery collection database, many of them in character.

Historical portraits of actors in character provide some of our best clues to understanding the performance style and celebrity of the celebrated stage performers of the early American stage, including vaudeville and Broadway.

Lillian Russell by Benjamin Joseph Falk, albumen silver print, 1889). (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

Q: Why is it significant that Kevin Spacey’s portrait shows him in-character?

Asleson: Kevin Spacey is a master shape-shifter, famous for his ability to inhabit fictitious characters and convincingly bring them to life. The stunning conclusion of the movie “The Usual Suspects” featured his transformation before our eyes from one character into another, with distinctive physical mannerisms to suggest an entirely different personality and psychology. What better way to pay tribute to his extraordinary gifts as an actor than by showing him practicing his craft?

Yeo has portrayed Spacey in a variety of his recent theatrical roles, including Richard III and Clarence Darrow, performed in 2011 and 2014, respectively, at the Old Vic Theater in London. The character of an American president seemed particularly appropriate for a Washington museum noted for its collection of presidential portraits.

Q: Speaking of the presidential portraits, what does this new (fake) president say about the presidency and how it is portrayed in popular culture?

Asleson: It says less about the presidency than about the chameleon-like ability of actors to inhabit and define the characters they portray, and of the ability of portraitists to pick up on and enhance the visual clues actors use to convey personality and psychology. Jonathan Yeo communicates the aggression and menace inherent in the character of Frank Underwood, for example, by exaggerating the size of Spacey’s shoe and drawing attention to his clenched fist. Actors make excellent subjects for portraiture because they are so skilled at externally representing and communicating interior states of mind and emotion.